Everyone knows about Marie Curie. The two-time Nobel Prize winner (one in physics and the other in chemistry – the only person to do so!), co-discoverer of radioactivity, and two elements in the periodic table: Radium (Ra) and Polonium (Po, named after her native country). Aside from her scientific scope, some other juicy tidbits about this woman would make any 1950s housewife clutch her pearls. For starters, she had an affair with a fellow physicist, Paul Langevin, in 1911. Langevin was a married man with four children, and gallivanting around with a widow was something that was not tolerated back in the day. Paris society was cruel to her, brandishing her with insults and asking her to return to Poland. Thankfully, she did have a friend in another well-known physicist with whom she could confide, Albert Einstein. But the real Curie I’m about to talk about is Irène Curie and her husband Frédéric Joliot. Later known as the Joliot-Curies.

Irène was the daughter of Marie Curie and, as such, followed in her mother’s footsteps and became a well-known chemist in her own right. Like her mother, she and her husband, Frédéric Joliot, worked as a team in the lab. Truthfully, their romance started when Frédéric began working in her lab, with Irene as his boss. Irène was the chemist, and Frédéric was the physicist. They were polar opposites; Irene was quiet and soft-spoken, while Frédéric was charming and was out to make a name for himself. Marie was not too fond of this match and would introduce him as “the man who married Irène.” The happy couple even changed both their last names to Joliot-Curie. I should be applauding his choice to hyphenate his name too, but I can’t help but feel like he really came out winning since now he had a much respected scientific family name to back him up.

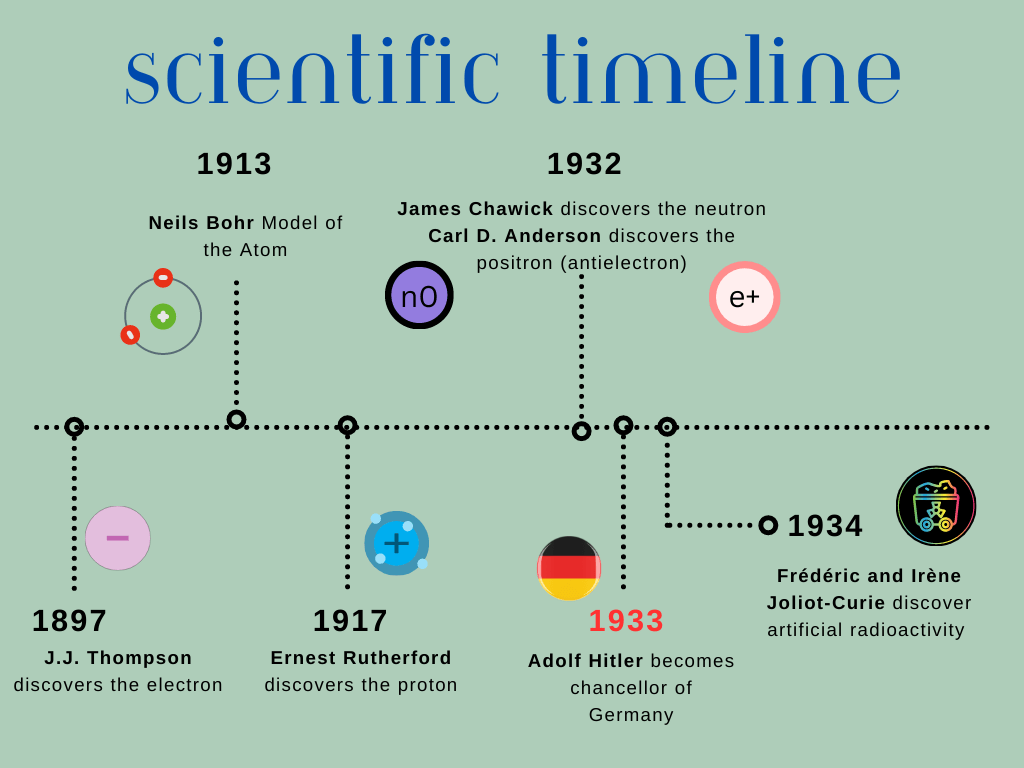

The year 1932 had been dreadfully hard for the Joliot-Curies. They had missed their chance to discover two subatomic particles; the neutron and the positron (antielectron). James Chadwick, the man credited with discovering the neutron, had read the published paper of Frédéric and Irène and thought there was something amiss. From that, he ran the same experiment with subpar instruments and materials to discover that what was actually being dispelled from the sheet of beryllium were neutrons. The second blunder was all on Frédéric; Irène’s chemistry was on point. Frédéric’s misreading of the spirals created in the cloud chamber led to them losing out on the discovery of antimatter-the positron.

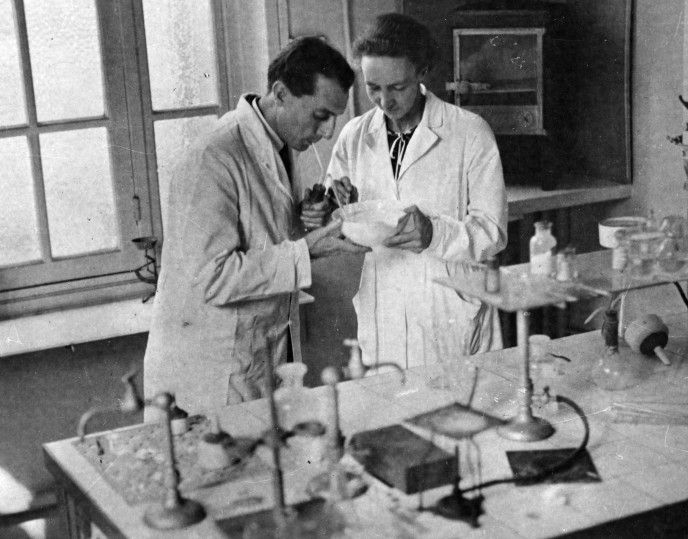

No matter (pun intended), it was after those two public blunders that their discovery of artificial radioactivity occurred. They went back to their lab to continue their experimentation of bombarding alpha particles to different sheets of metal. It wasn’t till they came on bombarding Aluminum (Al) with alpha particles that things started to get interesting. Their experiment of bombarding alpha particles (two protons and two neutrons) to a sheet of aluminum expelled neutrons and positrons. This was the first time a secondary shrapnel was produced. Frédéric then decided to take out the alpha particles altogether. Shrapnel continued to come, even after a good amount of minutes had passed. The Joliot-Curies had the counter checked to see if it was faulty equipment that was creating this interesting turn of events. All was good. The Joliot-Curies theorized that instead of loosing up and pushing out particles, the aluminum had in fact absorbed two neutrons. If this was true, then aluminum had become phosphorus, element 15.

Irène, a woman after my own heart, needed more proof. She needed to make sure that this was the case. The next day they went on to reproduce the experiment, but would then immediately after place the sheet of aluminum in a beaker of acid. If the aluminum had in fact transmuted to phosphorus the reactant would be phosphine (PH3). After the aluminum was put the beaker with acid, a bubbling of gas was produced. Irène was able to enclose the gas, and behold, it was phosphine. They had done it!

Now, because of their other two blunders they went one step further, they called upon Marie Curie herself. She was not well during this time, but she made the trip to the laboratory and with a wide smile confirmed their findings. Marie passed away a couple of months later on July 4, 1934. She never did get to see her daughter earn her own Nobel Prize.

The Joliot-Curies won the Nobel Prize in 1935. Science had taken a major leap, and the this new discovery would soon lead transmutations to be used in an explosive way.

Sources

Kean, Sam, 2019. The Bastard Brigade: The True Story of the Renegade Scientists and Spies Who Sabotaged the Nazi Atomic Bomb. Little, Brown and Company.

“Marie Curie and the Science of Radioactivity.” 2023. Aip.org. 2023. https://history.aip.org/exhibits/curie/scandal1.htm.

“This Month in Physics History.” 2023. @Apsphysics. 2023. https://www.aps.org/publications/apsnews/200705/physicshistory.cfm.

“Rutherford Model | Definition, Description, Image, & Facts | Britannica.” 2023. In Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/Rutherford-model.

“The Cloud Chamber: See the Invisible – Google Arts & Culture.” 2014. Google Arts & Culture. Google Arts & Culture. 2014. https://artsandculture.google.com/story/the-cloud-chamber-see-the-invisible-mus%C3%A9e-curie/dgVh31IaZkMGKg?hl=en.

“Alpha Particles | ARPANSA.” 2022. Arpansa.gov.au. 2022. https://www.arpansa.gov.au/understanding-radiation/what-is-radiation/ionising-radiation/alpha-particles.

One response to “The Road to the Atom Bomb: The Joliot-Curies”

[…] happened to understand physics and had befriended Frédéric Joliot; remember him? Since the Joliot-Curies used heavy water for their experiments, he was well aware that the German request only meant […]

LikeLike