Isotopes

The star of the movie, aside from the obvious titular character, Oppenheimer, is the use of isotopes. The very much talked about uranium-235.

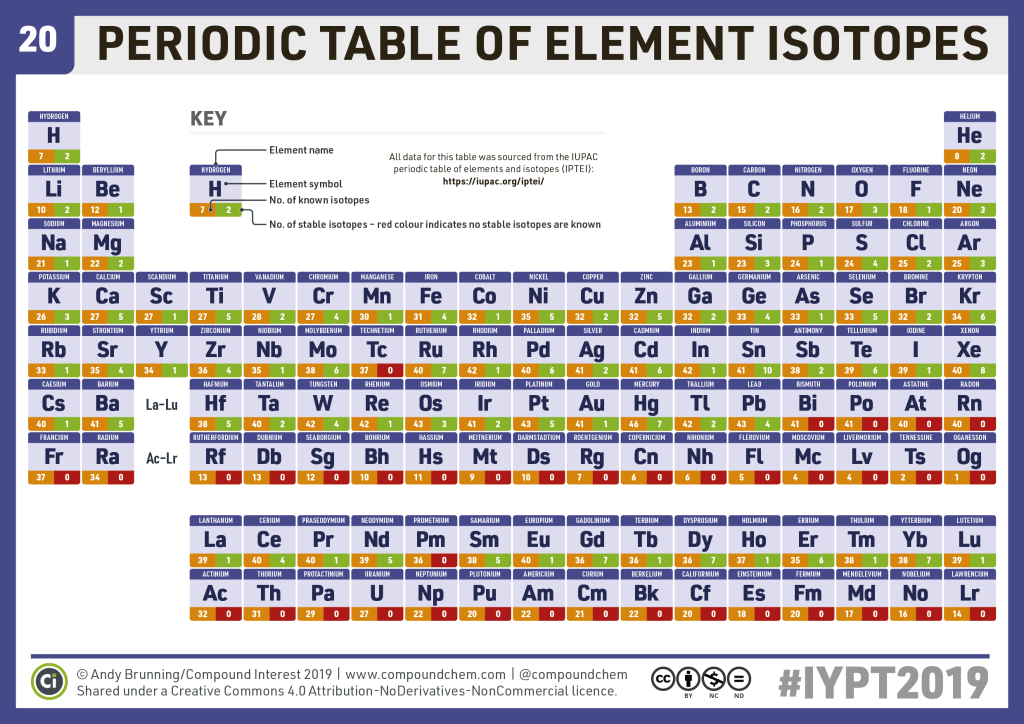

An isotope is a variation of an element with a different number of neutrons. Since an element’s identity and chemical properties lie in the number of protons, adding neutrons changes the mass of the element.

The majority of elements have more than one isotope. However, there is a reason that most elements do not have endless isotopes… nuclear stability! An overabundance of neutrons to protons can cause instability in the nucleus and lead to nuclear decay and possibly to a chain reaction.

With regard to uranium, we know that it is atomic number 92. This means it has 92 protons. Now, the famous uranium-235, has a total mass of 235 (protons + neutrons). This means that uranium-235 has 92 protons, and 143 neutrons. According to the stability chart below, its stability falls in the yellow band, denoting alpha decay. This alpha decay undergoes fission- the neutrons that smash themselves to the atom create an excitement that results in the splitting of the atom into two smaller atoms. One last thing about uranium-235; the most abundant kind of uranium is uranium-238. Just how rare is uranium-235? Well, for every 140 atoms of uranium atoms, there’s only one atom of uranium-235, making it very hard to obtain. Furthermore, to put another twist to it, Hitler came to possess large quantities of uranium once he took hold of part of Czechoslovakia.

Heavy Water (Spoilers Ahead)

There is a quick scene in Oppenheimer where Niels Bohr informs the rest of the scientists of what the Germans have been working on. One of them is the use of heavy water. The room has an obvious relief, but can you guess why?

Let us start with the fundamentals: Hydrogen has isotopes! Lo and behold, deuterium is a stable isotope. Deuterium is heavier, actually denser, having one neutron, a proton, and one electron. Denoted as D2O instead of the mundane and boring H2O (one proton, one electron, no neutrons). Heavy water is a key priming component for U-235. The additional neutron in D2O helps slow down the bombardment of neutrons and, unlike H2O, does not absorb them. However, we know that the most common uranium is uranium-238 (not the fissionable material of uranium-235).

Just as U-235 is rare, so is D2O, and much more so. During WWII, only one company produced this highly elusive compound, Vemork. Vemork is a hydroelectric power plant in Norway that had only sold eighty-eight pounds of D2O from 1934-1938. With Hitler’s new uranium acquisition, the need for heavy water was at the top of his list. When the plant received a request from Germany for their entire stock, plus the 220 pounds a month, red flags went up. It was known that heavy water had no real use for anything except for nuclear research.

A member of the general counsel for Vemork knew a French banker, Jaques Allier, who just so happened to understand physics and had befriended Frédéric Joliot; remember him? Since the Joliot-Curies used heavy water for their experiments, he was well aware that the German request only meant trouble. This resulted in one of the greatest heists that occurred after meeting the French banker and played out like a great James Bond movie. The bank authorized for Allier to spend up to 36 million francs in obtaining all the heavy water Vemork had available, screwing over the Germans. He set out with an alias and a vile of cadmium to be used as a last resort to contaminate the heavy water should they find themselves surrounded by Nazis. Once Allier arrived at the rendezvous point, a Vemork official told Allier that there was no need to pay them for the D2O. Allier knew that the Nazis would be tailing him, and so for the next couple of days he and his associate smugglers concocted a plan to export every cubic centimeter of heavy water out of Norway. Their plan culminated in using two airplanes leaving at the same time, parked next to one another on the taxiway. One airplane was headed for Scotland, the other to Amsterdam. The heavy water was put in the plane headed to Scotland, while a suitcase full of gravel was put in the plane headed to Amsterdam. The Nazis had failed to choose the correct plane, and once the heavy water arrived in Scotland, it was delivered to the cellar of Frédéric Joliot-Curie in France, where he would keep it safe from the Nazis.

Otto Hahn: The Splitting of the Atom

Otto Hahn and Lise Meitner

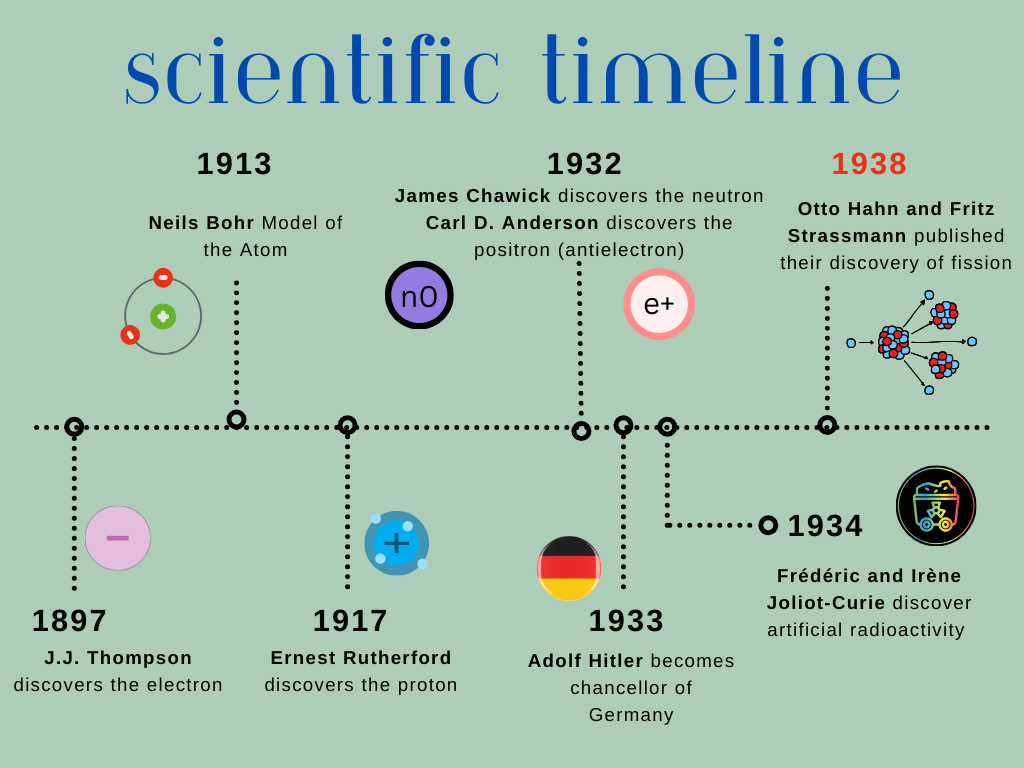

The splitting of the atom can’t be told without once again mentioning the Joliot-Curies. Yep, the same poor souls as before. You may have guessed it; their involvement is due to another missed opportunity for scientific history. If you haven’t already noticed, the scientific community was pretty cliquey and almost Mean Girl-like.

After the Joliot-Curies had won their Nobel Prize, Irène Joliot-Curie went on to work by herself while her husband decided to branch out from under her to work on a cyclotron. He was an ambitious man who wanted to make a name for himself and set out to do so by studying how subatomic particles interact.

Back to Irène, she went on to work on bombarding uranium and thorium with neutrons. Her results baffled her. She surmised that she could transmute them to other elements but could not definitively say what elements. The elements kept changing from one to another. Enter Otto Hahn, a German chemist who was not a fan of the Joliot-Curies, thanks to their previous publishing blunders. The inability of Irène to identify the elements made Hahn mockingly say that it was probably “curiosum.” Hahn ran into Frédéric at a conference in Rome, basically calling bullshit on Irène’s finding and for a retraction to the experiment and results that Irène had made. Frédéric, the gallant Frenchman (and a Nobel Prize winner) that he was, dared Hahn to prove her wrong.

Hahn jumped on the opportunity. He set out to redo Irène’s experiments. Guess what happened next? He too became stumped! What he saw was the expulsion of lanthanum and barium. Up to this point, it was understood that the bombardment of alpha particles and neutrons resulted in only breaking off small chunks of the nucleus. His results were denoting that the atom had split close to equal mass. Hahn needed help, so he went to the one person he knew was his intellectual superior, Lise Meitner. He wrote to her for help on this conundrum, and I’m sure he prayed that she would assist. You see, Meitner was Jewish and had to escape Austria and resettle in Sweden. Hahn and Meitner had worked together and when Meitner was outed as a Jew he had not stood up for her. This resulted in her nerve wrecking escape to Sweden. Now, he was asking for her help. Meitner, the brilliant and merciful physicist that she was, figured it out… Hahn had split the atom!

On December 22, 1938, Hahn requested a short paper to be published in Naturwissenschaffen (The Natural Sciences). In Oppenheimer, we see this scene play out with one of the grad students coming in and reading the news in the newspaper. Oppenheimer is in disbelief, and it can be said that from that moment in the movie, the metaphorical clock started for the race to create a nuclear weapon before the Nazis. In 1944, Hahn won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, along with Fritz Strassman. Meitner was not included—the unfair reality of being a woman and a Jew during this time.

Sources

Kean, Sam, 2019. The Bastard Brigade: The True Story of the Renegade Scientists and Spies Who Sabotaged the Nazi Atomic Bomb. Little, Brown and Company.

“#ChemistryAdvent #IYPT2019 Day 20: A Periodic Table of Element Isotopes.” 2019. Compound Interest. December 20, 2019. https://www.compoundchem.com/2019advent/day20/.

“20.9: Nuclear Fusion – the Power of the Sun.” 2016. Chemistry LibreTexts. March 11, 2016. https://chem.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/General_Chemistry/Map%3A_A_Molecular_Approach_(Tro)/20%3A_Radioactivity_and_Nuclear_Chemistry/20.09%3A_Nuclear_Fusion-_The_Power_of_the_Sun.

“Heavy Water Reactors – Nuclear Museum.” 2017. Nuclear Museum. 2017. https://ahf.nuclearmuseum.org/ahf/history/heavy-water-reactors/.

“Nuclear Magic Numbers.” 2013. Chemistry LibreTexts. October 2, 2013. https://chem.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Physical_and_Theoretical_Chemistry_Textbook_Maps/Supplemental_Modules_(Physical_and_Theoretical_Chemistry)/Nuclear_Chemistry/Nuclear_Energetics_and_Stability/Nuclear_Magic_Numbers.